“I learned from a young age that love hurts, yet it was one of my greatest longings.” – Reema Sukumaran

She wanted more than anything to be daddy’s little girl. But the outgoing father who seemed so loving towards other people, was a different man at home. He had a volatile temper and was extremely violent towards her and her brothers. Over the years, she witnessed her mother endure her father’s wrath as the family grew increasingly terrified of him. Surely life would get better when she moved out of the house and away from the abuse; it had to. Sadly, it didn’t.

Reema Sukumaran always longed to be a mother as a little girl. God answered her prayers and blessed her with six boys whose ages range between 14-24.

“I identify myself as a stay-at-home mom who doesn’t stay home,” Reema told The Weight She Carries. “I am also a wife to an amazing husband who has been with me on this incredible journey.”

The incredible journey Reema is talking about stems from a childhood marred by tremendous physical and emotional abuse at the hands of her father.

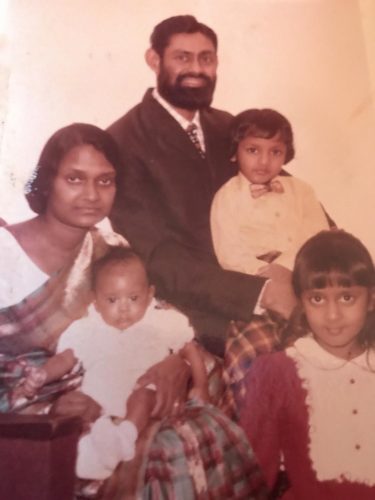

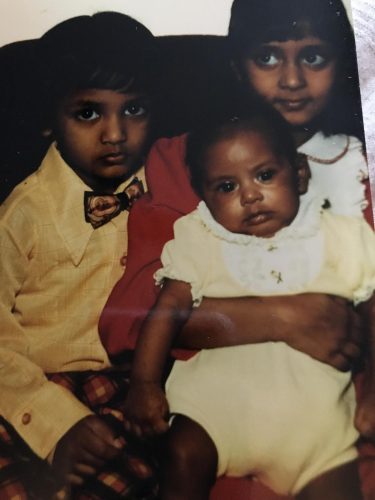

Reema’s parents migrated to Canada from India when she was about two years old. Like many immigrant families, her parents were working hard to build a life in a new country. Reema, being the eldest of three children, chipped in too by handling many of the household chores and taking care of her younger brothers.

From the outside looking in, life appeared normal for this young family.

“There were many ups and downs that came with [being immigrants], but I realized that it wasn’t normal to have a dad who was so extremely physically violent with his wife, and then eventually with the children,” she said.

Reema’s mother was considered an older bride when she got married. During their courtship, Reema’s father was emotionally abusive towards her.

“I don’t think my mother recognized it,” Reema said. “I think she was naive to that. He would tell her things like she was dark-skinned [so] nobody would want her, and how lucky she was to have him.”

At one point, before their wedding, Reema’s mother confided in her own father and told him she didn’t want to marry the man she was betrothed to.

Reema’s grandfather said he would help her but died about a week before the wedding.

“He didn’t have a chance to help her and I think my mom truly felt trapped, so she went ahead and married my father,” Reema said.

Early on in the marriage, the emotional abuse turned physical, Reema said.

“My mom tells a story of how I was just a year old and sitting on my dad’s lap and hitting his head as babies do in play. He lost it, took his knuckles and hit me on my head, ‘You don’t ever raise your hand at your father,’ he said. That was the first sign of physical abuse that I’ve heard.”

– Reema Sukumaran

Over the years, her father’s violence increased. While Reema doesn’t recall her father physically abusing her mother until she was in high school, she believes there were many violent incidences before then.

“She was terrified of his temper. When he was losing it, his voice would escalate and she really reacted to that,” Reema said. “The fear was constant. My mother would [always] reprimand us quietly so as to avoid triggering my father. So from a very young age, we knew that my dad was volatile. It was a fear we all lived with.”

Prompted by her doctor to seek help after he noticed signs of abuse, Reema’s mother found the courage to open up to a family member, but it was to no avail.

“That person actually told her, ‘We don’t leave our spouses. That is not what we do in our family.’ After that point, my mother never shared her pain with another person. It was in the early 70s. It’s really something I’ve struggled with because when my mom reached out, if somebody had helped her, our lives would have been drastically different.”

– Reema Sukumaran

Reema became her mother’s partner and support system – a role psychologists refer to as a parentified child, Reema explained.

“I was my mom’s best friend and I felt like we were all in it together,” she said. “Battered women are often almost [too] paralyzed to leave because there is so much fear – fear of stigma, especially what people are going to say. My dad had such control over her and threatened suicide one time when my mom took us to my aunt’s place.”

As Reema got older, she would beg her mother to leave when her father beat her and her brothers. The effects of the abuse impacted her more profoundly in her teenage years.

“At some point, I lost respect for my mother,” Reema said. “I love her, but I just didn’t understand her actions. Although she did many things for us, the one thing I wanted my mom to do was to protect us from our dad, but she was unable to do that until much later. So I had a lot of anger towards my mom from hurt.”

“As a child, Jesus was my invisible friend because I had nobody else to turn to. A lot of times I would pray and ask, ‘After this fight, can we be a happy family?’ At some point I realized that was not going to be a reality. My mom never fought for herself. She fought to save her marriage, but she never fought to be happy. That’s something that breaks my heart. I wish she had fought harder for herself.”

– Reema Sukumaran

When she finished high school and went to university, Reema felt a sense of freedom as she embarked on a new chapter in her life. During her final semester, she did her student training and decided to go back home. It was a Christian School and one of her brothers was good friends with a chaplain at the high school.

“My brother had confided in him about what was going on at home. The pastor was very loved, very charming and charismatic. He could preach powerful sermons that would make you truly believe that Jesus is coming, and you wanted to have a relationship with him,” she said.

The pastor was very physical with students and it wasn’t uncommon to see students sitting on his lap or him kissing them on the cheek. It appeared to be the norm and no one seemed to question it because he was so loved and trusted, Reema said.

The pastor embraced Reema, too, and became someone she and her family grew to love. Since he was close to her family, she would offer to babysit for him and his wife, who worked as a nurse.

“One evening he came home when I was babysitting and put his son into the bathtub. He began to chat with me which wasn’t something out of the norm. I was sitting there and all of a sudden, he pushed me down and pinned me under his body. My hands were trapped and he began forcing himself onto me. He didn’t even take my clothes off. I was so skinny back then that he went through the leg of my shorts. I begged him to stop and told him that I was a virgin and that he was hurting me. His reply was, ‘I won’t go in all the way.’”

– Reema Sukumaran

“I’m not sure how I made it home that night. I had driven there, so obviously I drove back home,” Reema said. “I remember going into the bathroom, sitting on the toilet and looking down at my underwear and seeing blood. I realized I had lost my virginity. I had just been raped by my pastor – somebody I trusted. I was 22 at the time.”

Reema left the bathroom and stood by the mirror in front of her dresser. The shock began to wear off and morphed into rage that surged through her body.

“I didn’t think to tell my mother in that moment because I was upset with her about stuff that had been happening at home. I thought to call the police, but I quickly remembered I couldn’t call them because they had not helped us in the past,” she said.

A few years earlier, Reema’s brother had been in the bathroom and dropped the toilet seat lid after flushing the toilet. The sound triggered her father. He grabbed her brother, locked the door and proceeded to beat him mercilessly.

Reema’s mother begged her husband to beat her instead of their son. Reema ran to the kitchen, got a butter knife from the drawer and her mother managed to unlock the bathroom door. Her father released her brother, grabbed Reema’s mother by her hair and began beating her instead with a piece of wood.

Mortified, Reema called the police. Despite the black and blue bruises all over her mother, the police didn’t help. They ended up sitting at the table with her father discussing how difficult wives could be.

Calling the police to report the rape was no use, Reema resolved. They hadn’t helped then, why would they help now?

“I ended up just being quiet and trying to figure out how this happened. Was this my fault? I blamed myself,” she said. “I didn’t share it with anyone for about a month or so. Then I did confide in a few friends. But looking back, we were so young that no one knew what to do or say.”

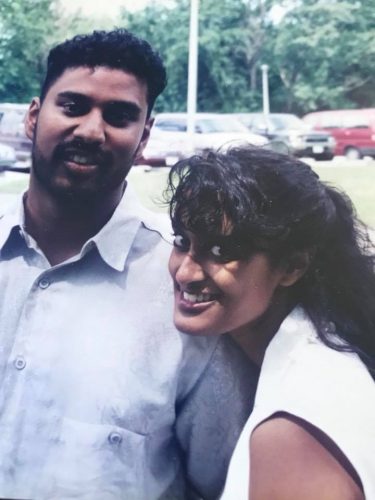

A few months later, Reema returned to her university to graduate. One of the people she confided in was her then-friend Sanjeev. Following a seven-year friendship, the two began a romantic relationship.

As the couple prepared to tie the knot, they sought the advice of a marriage counsellor whom they opened up to about the rape.

“Our counsellor [who was also a pastor] told me I needed to do something about the rape; that I couldn’t just sit back and bury it. He had me call my rapist and tape him. It was one of the hardest things I’ve had to do,” she said. “I was petrified. He was still part of my everyday world.”

During the conversation, Reema confronted him about raping her. Afterwards, the pastor who was counselling the couple called the principal of school and the church leadership to inform them.

Initially, the pastor denied raping Reema, but when he was told there was a tape recording, he changed his tune and said the act was consensual.

“At that point, he resigned and we asked that he lose his ministerial license. But at the same time, the principal of the high school gave him a glowing [recommendation] and they allowed him to write a letter to the community,” she said. “In his letter, he made mention that around the time his mother died, a young lady had come into his life and she – meaning me – had taken advantage of him. This was something they allowed him to send to the school community, and people believed him, of course.”

No one in the Church’s administration reached out to Reema. She tried to follow up but got shut down by numerous administrators in the church. Over time, she determined that there was nothing more she could do.

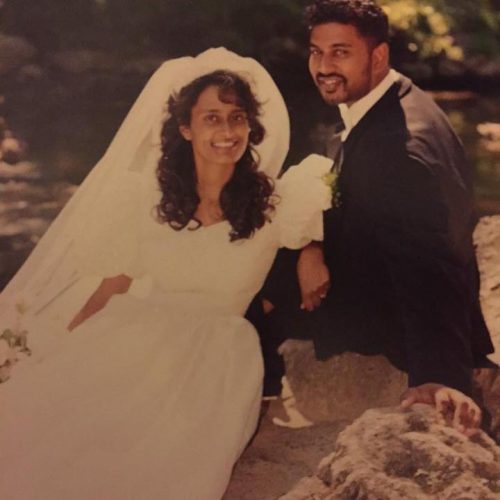

Reema got married and settled into life as a wife, and soon after, a mother. Not knowing what to do with the pain, she asked God to use it somehow and put it in the back of her mind.

Twenty-five years went by.

About four years ago, Reema’s youngest brother called and asked her if she would share her story at a pastors’ training session in British Columbia, Canada. She agreed and was initially excited about the engagement, but as the date approached, she became increasingly nervous.

“I went there petrified because I was speaking to a room full of pastors. I shared my story and ended by saying, ‘It’s been 25 years and no one from my church cares to this day. Nobody reached out to me or said they were sorry. And yet a lot of people knew.’ I sat down with tears in my eyes. The president of the conference took the mic from my brother, walked up to me and said, ‘You want an apology from the church? I, as a minister of the Gospel, am sorry.’ I started crying uncontrollably. It was a very powerful moment.”

– Reema Sukumaran

That’s when healing began for Reema. The band-aid had been ripped off and she was now ready to start dealing with the pain that had been buried for so long.

The Canadian Union, which serves the church of North America, had no connection to her situation but offered to pay for professional counselling for Reema, which is still ongoing.

“I thought the darkest days were right after the rape, but I was wrong. The darkest days were yet to come,” she said.

Everything came to a head three years ago when her father died.

“Darkness took over for me and I believe that led to a mental breakdown. I couldn’t walk alone, I couldn’t be alone in a room in the house and I ended up having a seizure which was unexplainable. I also had panic attacks, so it was just this nightmare that we were living through,” she said. “Sometimes I just wished God would take me.”

After years of unrelenting pain and darkness, Reema’s breakthrough finally came during a praise and worship session at her church one Saturday. As the congregation sang the song “Jesus”, Reema began to weep inconsolably. Her friends rallied around her and began to pray.

“I just wept. That was the beginning of God healing me. A few years went by and it was now the one-year anniversary of my seizure,” she said. “I realized that my panic attacks had stopped and that I was feeling much better. It was not a miracle that happened overnight. It was a long journey and continues to be a journey.”

Medication has played a part in her healing. She came to the realization that she was so broken that her brain needed medication cope with the immense traumas she had lived through.

“I don’t know why it took 20-something years for this to come out, but it did. I’ve been working with my therapist and every day is a struggle. I still have fears of ‘the boogeyman’ coming and getting me. It’s something I continue to work through,” she said.

Nothing has happened to the pastor who raped her. Although he is not pastoring anymore, he has since received a chaplaincy license and works at one of the main hospitals in his region. He preaches in church, not as a pastor, but as a motivational speaker.

“What I’ve learned is that churches are broken. It’s not a specific church that has this issue; it’s all over. People in leadership are broken,” Reema said. “As far as my rapist is concerned, God is dealing with him. I have learned to have empathy for him, and I feel very bad for him because his salvation is at stake. He has never apologized. It’s something I do long [for] from him but I’m not holding my breath anymore.”

As Reema continues to heal, her prayer is that God uses her pain to help others.

“God has given me the courage to speak out and be the voice for so many women and men out there who cannot use their voice. I just want so badly for them to know that they are not alone. Each of our experiences is different, but ultimately, we are these broken people and my voice is sharing their story. And I just want my strength to seep into them so they can know that there is hope.”

– Reema Sukumaran

Vimbai E. is a content marketer, ghostwriter, and the founder of The Weight She Carries. With hundreds of articles and stories publishing online, in print and for broadcast, her love of language and storytelling shines through every piece of writing that bears her name.